Barriers and Opportunities to Improve the Implementation of Patient Screening and Linkage to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Primary Care

Abstract

Although pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective at preventing HIV infection, only around 25% of at-risk individuals in the United States have accessed a prescription. One way to increase PrEP uptake is through the sexual health screening of patients and linkage to PrEP in primary care settings. The objective of this analysis was to assess the barriers and implementation strategies during a screening and linkage to PrEP pilot intervention. Primary care patients were screened for PrEP indication during routine primary care visits. Of the 1,225 individuals screened, 1.8% (n=22) were eligible for PrEP and from those, 77.3% (n=17) attended the specialist appointment and were prescribed PrEP. Primary care patients (n=30) and providers (n=8) then participated in semi-structured interviews assessing their experience with the pilot intervention. Using an applied thematic analytic approach, patients and providers identified barriers and related improvement strategies that could be classified into four main categories: 1) Financial Barriers: Individual- vs. Clinic-level Considerations 2) The Role of Stigma, Discomfort, and Cultural Factors 3) Logistical Hurdles and Streamlining the Intervention, and 4) The Lack of PrEP Knowledge and the Need for Education. Findings support the accepatability and feasibility of screening for PrEP in primary care along with appropriate implementation strategies. This study suggests that because of the high volume of patients seen in primary care, sexual health screenings and linkage to PrEP interventions have the potential to reduce new incident HIV infections among diverse sexual minority men.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Denise Evans, Epidemiologist, Clinical HIV Research Unit, Helen Joseph Hospital, Houghton, South Africa.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2022 Carrie L. Nacht, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective in preventing HIV infection and is now being widely promoted as a prevention strategy for individuals perceived to be at high risk for HIV.1,2 However, only about 25% of sexual minority men (SMM) who are likely to benefit from PrEP currently have a prescription.3 Among SMM, racial/ethnic minority SMM have been shown to have a disproportionate risk for HIV infection, and uptake of PrEP has been disproportionately slower compared to their White peers.4 Because of the high volume of racially and ethnically diverse patients who visit primary care for health services, routine HIV risk screening and referral for PrEP in primary care settings has the potential to further reduce disparities in HIV infection rates in the United States.5

Previous studies examining barriers to providing PrEP in primary care settings have found multiple barriers reported among primary care providers (PCPs). Some PCPs have reported that they avoid prescribing PrEP due to concerns about the cost of PrEP and related medical and lab visits for patients,6, 7, 8 while others have cited concerns about patients’ ability to adhere to their PrEP regimen.9 In particular, concern for adherence was a perceived barrier to prescribing PrEP to patients engaged in perceived high-risk behaviors (e.g., persons who use or inject drugs, with multiple partners, exchange sex for money, or who are unstably housed).10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Prior work has identified a lack of knowledge of current clinical guidelines for providing PrEP15 and disagreement on whether PrEP should be provided by PCPs or HIV specialists.9, 15, 16, 17, 18. Although guidelines that promote sexual health screening and provision of PrEP in primary care have been developed and made widely available,5 the majority of PCPs report that they do not regularly screen for sexual-risk behavior among their patients.19, 20, 21 Because of the volume of patients attending primary care, the ability to rapidly determine PrEP eligibility, provide education and consultation around PrEP, and provide, or refer patients for, PrEP is an important and often missed opportunity for intervention.

The current study sought to assess the barriers observed during the implementation of a brief PrEP eligibility screening and linkage to PrEP intervention piloted in two primary care clinics nested within a large integrated healthcare system. This brief intervention was designed to be conducted by asking all male-identified patients to fill out a brief screening questionnaire that assessed for possible HIV risk factors when they were checked in for their appointments with primary care providers. Providers would check the screener for completeness, determine eligibility for PrEP, and provide eligible patients with a referral to HIV specialty services for a PrEP appointment.

This study was among the first to pilot a brief PrEP screening and linkage intervention in primary care. The objective of this qualitative analysis was to examine the barriers experienced by both patients and providers during the pilot intervention and to assess the overall acceptability, feasibility, and opportunities for improvement.

Materials and Methods

Intervention Overview

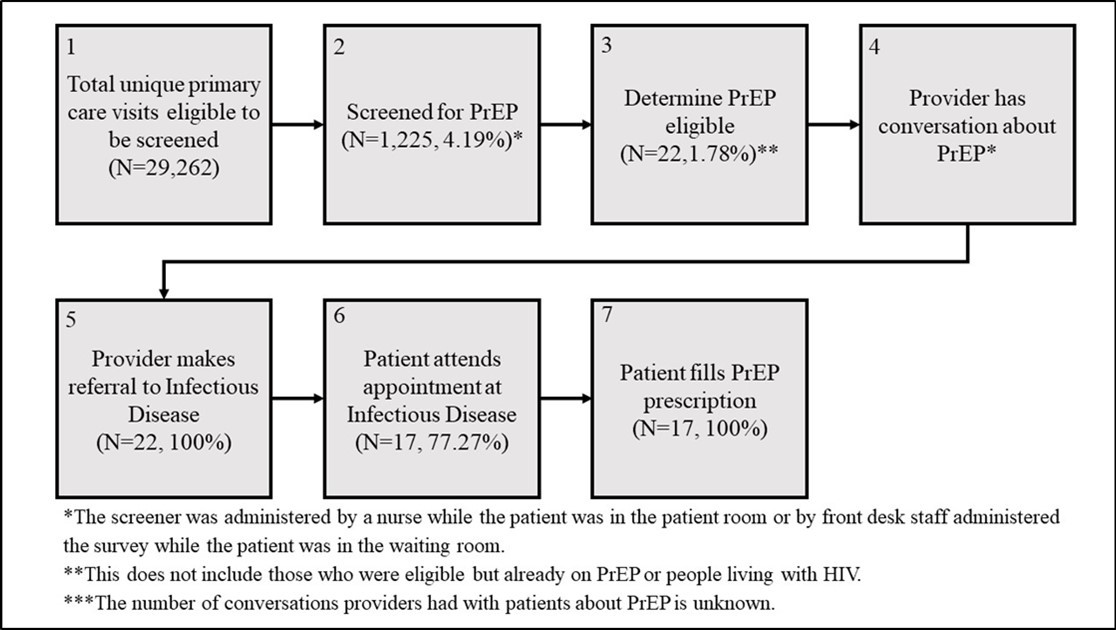

The study utilized a proof-of-concept approach to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the pilot project: Screening and Linkage to PrEP (Project SLIP).22 The overall protocol for the pilot study has been described in detail in a prior publication.22 Briefly, a 6-item sexual risk screening instrument for facilitating PrEP uptake was developed and integrated into the workflow of two primary care clinics contained within a large, integrated health system, Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC), as part of Project SLIP. At KPSC, PrEP is primarily provided with HIV specialty care services.22 Kaiser Permanente provides care for over 9 million Californians.23 Providing screening and linkage to PrEP from Kaiser’s primary care clinics could greatly extend PrEP services to many members of communities at risk for HIV. Because of the limited scope of this pilot, patients whose electronic medical records indicated cisgender male identity aged 18-65 were to be screened for PrEP indication during their routine primary care visits over a 12-month implementation period. Patients who screened as eligible for PrEP were then referred to an HIV specialty care services for further PrEP evaluation and prescription as per the protocol for providing PrEP at that time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.Overview of the screening and linkage to PrEP pilot study, Project SLIP.

Interviews with Primary Care Providers and Staff

Semi-structured in-person interviews were conducted with providers and staff (e.g., primary care doctors, nurses, medical assistants, administrators, and front desk staff; n=8). Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes (range: 45-75 minutes) and were conducted in English by the study principal investigator (ES). Interview questions focused on (1) experiences around discussing sexual behavior and substance use with patients, (2) attitudes about providing PrEP as an HIV prevention intervention for SMM, and (3) factors that would make it easier or more challenging to screen and refer SMM for PrEP (“How best do you think this routine screening can be integrated into your clinic workflow? (Probe: When should it be administered? Who should conduct the screening and collect the form? Who should be going over the result of the screening with patients?)”). Information about provider demographics, specialty, and related experience providing care to SMM was collected through brief surveys at the end of each interview.

Interviews with Patients

Semi-structured phone interviews were conducted with patients who screened as eligible for PrEP (n=30). Patients were stratified by eligibility and referral outcomes; 8 patients were interviewed who were not eligible for PrEP, 13 were interviewed who were eligible for PrEP but who did not start PrEP, and 9 were interviewed who were eligible for PrEP and did start PrEP treatment after referral. Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes (range: 45-75 minutes) and were conducted in English by three members of the research staff (AM, DLG, and JMC). Interview questions focused on (1) comfort with screener questions and ease-of-use (“What did you think about the specific questions on the questionnaire?”), (2) experience with consultation for PrEP with PCP (“Did your doctor talk with you about PrEP at your last visit? If yes, how did you find this experience?”), (3) factors that made it easier or more challenging to attend the PrEP appointment at HIV specialty care services, (4) experiences during PrEP evaluation and prescription fill, and (5) reasons for/against starting PrEP treatment. Patient demographics were collected via a brief survey administered at the end of the interview.

All interviewees provided informed consent to participate in the study and patients received $50 for their time. Study procedures were approved by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California and RAND Corporation institutional review boards.

Data Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified. The research team used an Applied Thematic Analysis approach to identify key themes across the interview data.24, 25, 26. The coders (led by JF, including SM) first read six randomly selected transcripts (n=4 patient, n=2 provider) and wrote and applied analytic memos on their initial ideas about key topics and patterns in the data.27 The coders then generated a preliminary codebook and independently coded four randomly selected patient interview transcripts Using Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software NVivo (released March 2020).28 The coders had an average of >85% agreement in the coding application, suggesting a high level of reliability from the outset.25, 29.They then resolved discrepancies, revised the codebook, and individually coded the remaining 24 patient interviews before repeating this coding process with provider interviews. Once all data were coded, the coders developed code summaries (synthesized, high-level summaries of excerpts for a single code) for a selection of relevant codes. The research team then identified key themes and sub-themes through group discussion about coding patterns in the data, with attention to barriers and opportunities for improvement in the implementation of the intervention.24-26

Results

Overview

Thirty patients were interviewed as part of this study and had a median age of 30.5 (range 21-66). Patient participants identified as Hispanic/Latino (26.7%), Asian (6.7%), Black/African American (10%), White 8 (26.7%), and other race (20%), and the majority (70%) identified as gay (Table 1). The eight provider and staff participants consisted of front desk workers (12.5%), administrators (25%), nurses (37.5%), or primary care medical doctors (25%). Demographic information for providers is not provided due to the small number of participants and concern for anonymity.

Table 1. Demographics of Patient Participants| Characteristics | All participants(N=30) | Eligible for PrEP & linked to care (N=9) | Eligible for PrEP but not linked to care (N=13) | Ineligible for PrEP (N=8) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 32.5 (10.4) | 32.2 (11.0) | 31.25 (6.8) | 34.2 (13.0) |

| Race/ethnicity* N (%) | ||||

| White | 8 (26.7) | 3 (10) | 3 (10) | 2 (6.7) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 8 (26.7) | 3 (10) | 4 (13.3) | 1 (3.3) |

| Black/African American | 3 (10) | 0 | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Asian | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0 |

| Other | 6 (20) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (10) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Decline to state | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) |

| Sexual identity N (%) | ||||

| Gay | 21 (70) | 6 (20) | 12 (40) | 3 (10) |

| Bisexual | 3 (10) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) | 0 |

| Straight | 5 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 5 (16.7) |

| Queer | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 0 |

Based on the full sample of participants eligible to be screened during the 12-month study period (Figure 1), N=1,225 individuals were screened, 1.8% (n=22) of whom were eligible and referred for a PrEP appointment with an infectious disease provider (this does not include those who were eligible but were already on PrEP or living with HIV). Of the 22 who were eligible and referred for a PrEP appointment, 77.3% (n=17) attended the appointment and filled the PrEP prescription at the KPSC pharmacy within 5 days.22

Thematic Findings

Based on the interviews with patients and providers, there were several barriers to implementing the screening and linkage intervention as well as suggested opportunities for improvement at each step in the Project SLIP screening and linkage to PrEP process. While these two groups aligned in some of their feedback, they also diverged substantively in their focus on certain barriers and opportunities. In general, patients tended to discuss the individual-level factors that impacted their experience and opinions around taking PrEP, whereas providers focused more on system-level factors impacting their ability and willingness to screen and link primary care patients to PrEP. In the next section, we present four thematic categories highlighting these barriers and opportunities: 1) Financial Barriers: Individual- vs. Clinic-level Considerations, 2) The Role of Stigma, Discomfort, and Cultural Factors, 3) Logistical Hurdles and Streamlining the Intervention, and 4) The Lack of PrEP Knowledge and the Need for Education (Table 2) and visually depict how each thematic category manifested across the stages of the screening and linkage to PrEP intervention.

Table 2. Comparing patient and provider illustrative quotes across emergent themes| Theme | Patient Illustrative Quote | Provider Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Barriers: Individual- vs. Clinic-level Considerations | “I’m paycheck to paycheck at this point, so I don’t have the extra $900.00 to continually, to even float for the first time. That’s really the issue.” (35, White, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP) | “I will tell you that if you want to have somebody who's a case manager linkage (coordinator)_, you're going - you're going to have to find funding for another person to do this…Because everybody is - so we're very understaffed…But I do think it can be done and there can be a worker that can absolutely set them up and do that. Absolutely that can be done. You just need another staff member to do that.” (Primary Care Doctor) |

| “There are ways of scheduling around your appointments, making sure that you have metro fare to get to the appointment or that you have knowledge and the resources to sign up for a copayment program.” (25, other race, queer, linked to PrEP) | ||

| “If you go into it and the prescription is like free or really cheap and it protects you, I think more people would go and look for it.” (31, Asian, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP) | ||

| The Role of Stigma, Discomfort, and Cultural Factors | “If I was living at home or, you know, living with my family, taking PrEP might be more difficult because it prompts conversations that I just have not traditionally felt comfortable having with my family.” (34, white, gay, linked to PrEP) | “Maybe (the screener) can be something that we initiate in the room. Like have them fill it out in the room and then maybe the doctor can review it with them, so that they're a little bit more comfortable and they're not like… ‘I'm filling this out in front of everybody here. Everyone's going to see what I'm writing.’ Because I mean it does ask questions that are very sensitive towards your sexuality and some of them are not comfortable.” (Primary Care Medical Assistant) |

| “Discussing sexual health with somebody when I know that they're like a gay doctor that somehow puts me more at ease…you know that they're going to be more familiar with some of the issues you're talking about or potentially less judgmental about it.” (34, white, gay, linked to PrEP) | “There were like maybe one or two doctors that probably had some reservations about (the screener), as well…Like being able to answer those questions (that patients had about the screener). But I think during that meeting, we were able to get a little bit more information to help that physician feel comfortable having those conversations.” (Primary Care Medical Assistant) | |

| “Providers should probably be members of the queer community. That would be a lot more helpful, because the last thing I need is someone that’s a heterosexual, cisgendered male telling me what the fuck to do with my sexuality and counseling me when he literally is not even an ally. So, someone that identifies as a queer ally is very important, I believe, because I can actually take them seriously and they will actually take me seriously.” (25, Hispanic/Latino, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP) | “I think also you know, (the nursing staff)’s own personal beliefs on the subject may come into play…You know, maybe they’re not, you know, maybe the way they were raised was not, you know, something that they’re not comfortable discussing the subject (I think also you knowof sexual health)…Most of the time, these sorts of subjects are reserved for the doctor…it’s not something that I think the nursing staff is accustomed to.” (Primary Care Nurse) | |

| “I think that anytime that you engage in a conversation about sexual health among men and you know that they’re not queer, themselves, it’s uncomfortable.” (36, Hispanic/Latino, gay, linked to PrEP). | ||

| “Specific training around the gay community, especially for those that don't identify as homosexual, can really improve the connection and their relationship that they have with their doctor.” (29, Black, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP) | ||

| Logistical Hurdles and Streamlining the Intervention | “The clinic did reach out to me to schedule an appointment, and I told them I could not make it at that time. And then we never were able to reschedule an appointment. I didn’t have their contact information, and when I tried to get the contact information from my medical care provider, I could not get it.” (25, Hispanic/Latino, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP) | “I would say the barrier will be because like most of the time, you know, we all are short of staff.” (Primary Care Front Desk Staff) |

| “Make it as convenient as possible. It’s probably something difficult for people to decide and having something be a little further away or a little harder to get an appointment, any excuse to give people to not make an appointment or get more information…you want to eliminate that as much as possible. So, I’d probably make it easier than normal to get more information.” (35, other, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP) | “There would need to be like a physician meeting where all of the doctors were there to introduce — to introduce (the study). And say, ‘This is something we want to bring here.’ Once we get all the doctors on board, we then would have a second meeting with all of our nursing staff. And then maybe bring in, if there’s a physician champion that wants to own it, to own this pilot…if there are any questions or barriers, they can be a representative of what the physicians want.” (Primary Care Administrator and Nurse) | |

| The Lack of PrEP Knowledge and the Need for Education | “I didn't do a whole of research and I’m not completely informed about the medication itself, and I guess the idea of taking medication for something that you don’t have kind of made me pause.” (39, White, gay, ineligible for PrEP) | “I think the back part (of the document provided by the intervention) was more informative. I thought maybe if we just tried it with information, kind of soften it, the whole - then kind of - then go in for the questionnaire. Maybe that kind of can mentally prepare them as to where this is going.” (Primary Care Nurse) |

| “Having some kind of a youth group meeting…where new users or potential users could actually talk to folks who are already using it in an open environment, so that they could have their questions answered. They could see actual people who are using (PrEP) and benefiting from it and hear from first person accounts and how it’s helping them protect themselves...that would be a way of reassuring first time users that this is a safe and effective treatment.” (37, other race/ethnicity, straight, ineligible for PrEP) | ||

| “If you have a partner that has HIV, you can also benefit from (PrEP). So, that's something I didn't know. So, again, it's - it's an advertising, right? ...So, I think just educating the patients, letting them know it's not just certain type of your - this sexual orientation and like you could benefit from it, you know?” (Primary Care Nurse) |

Financial Barriers: Individual- vs. Clinic-level Considerations

Costs surrounding attending PrEP appointments, time off work, copays for prescriptions, and labwork were often cited as barriers among patients, while system-level costs to implementing intervention among providers We identified a clear divergence between how patients and providers described the relevance of financial cost in their experiences and perceptions of the intervention. For patients, the cost of a PrEP prescription was the most prevalent barrier to both attending their clinic visits and filling their PrEP prescription; indeed, this was discussed by nearly every patient at length.

Patients disclosed a wide array of individual-level financial barriers affecting their ability to attend clinic appointments, such as having to take off work to visit the clinic (i.e., lost wages), and transportation-related costs (e.g., gas, parking, etc.). For example, one patient discussed the role of transportation barriers related to parking costs:

“Having to pay to park there is kind of like, iffy…I just feel like I’m already paying a ton of money to be a patient, so when you still want to charge me to park there…Maybe charge a little less or make it free.” (29, Hispanic/Latino, Mexican, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP)

A particularly common strategy suggested by patients to improve this intervention was to reduce financial costs, including ensuring that the PrEP prescription be free to fill or, at a minimum, significantly less expensive. One participant discussed this need in the context of patients who are economically disadvantaged, such as those who are in school:

“The fact that people have used PrEP as a defense tool for your health definitely has to do with where you are economically, where you land on the income bracket. So, for a college student, it has to be free. For somebody who has just come out of college, there has to be assistance. For somebody who is deep in their career and they know what’s up, they’re not going to think twice about it.” (36, Hispanic/Latino, gay, linked to PrEP)

The idea that patients had to choose between different forms of preventative care because of cost was identified several times. One patient explained how condoms may be a better option for some:

“We usually think that buying condoms, that’s not too expensive and it’s probably going to be a good way to kind of prevent any sexually transmitted diseases, and that’s probably a lot cheaper than medication, so that could be one reason I wouldn’t go for PrEP.” (28, other race, straight, ineligible for PrEP)

Thus, a financial barrier to starting this intervention may be that other forms of preventative care may be more cost-efficient.

Despite the multitude of financial factors that patients discussed as relevant barriers to accessing PrEP, providers did not discuss many perceived individual-level financial barriers for patients. One provider suggested that: “this intervention should be done in clinics that are more in lower-income areas” (Primary Care Doctor). That financial barriers were not discussed often by providers (and, as in the above instance, not discussed at length or with nuance) suggesting some providers may lack awareness of the actual or perceived cost to patients of accessing PrEP within the healthcare system. Providers may also be unaware of additional costs (e.g., transportation, parking costs, time off work) incurred in the process of acquiring PrEP.

On the other hand, providers more frequently discussed system-level financial barriers such as the cost of additional staff time to complete the screening and linkage intervention components. One physician explained that while there could be a staff member to support the intervention, there would need to be new funding to support this role/work:

“If you want to have somebody to do the intervention you're going to have to find funding for another person to do this…we're very understaffed.” (Primary Care Doctor)

The clinic funding and staffing shortages were observed barriers to implementing the screening and linkage intervention. Multiple providers interviewed discussed staff turnover and the need to continuously train new staff (and rotating residents) on Project SLIP, which did not consistently happen, especially when clinics were busy:

“The PrEP intervention is a lot to cover…that actually can be one of the biggest challenges. When you have new members coming in.” (Primary Care Administrator and Nurse)

This study suggests that it is important to consider that the financial costs associated with conducting a screening and linkage to PrEP intervention may be perceived differently by patients and providers and that educating providers about the costs impacting patients might be important for intervention success.

The Role of Stigma, Discomfort, and Cultural Factors

Patients and providers both described stigma as a barrier to this intervention, but at different time points in the screening and linkage to PrEP prescription process. Some patients discussed how their responses to the screening items could lead to feelings of shame or stigma related to identifying as a sexual minority.

“People might feel shame and guilt associated with, like, when they’re taking the questionnaire, it might cause those feelings. So, it might provide dishonest responses on a questionnaire.” (25, Hispanic/Latino, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP)

Several participants who identified as sexual minorities mentioned fear that being screened or evaluated for PrEP would potentially disclose their sexual identity without their consent. Some patients discussed being fearful of PrEP showing up on their insurance, and fear that being on PrEP could get back to their parents or be made public knowledge.

“I’m still on my parents’ health insurance, and if PrEP were to show up on that, I don’t know how they would react, and I don’t know how I would feel about them knowing.” (24, other race, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP)

Some patients also identified stigma as a barrier to discussing their sexual behaviors, identity, and history openly with their provider during the initial PCP visit. Some patients voiced discomfort discussing these aspects of their lives given how societal norms have conditioned them to keep their sex life private. One patient highlighted how important it was for them to have a doctor who also identified as a member of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community during the primary care visit as a way to increase comfort in discussing sexual health and the use of PrEP:

"I specifically called and asked for a gay doctor, so he can know about a gay man’s health, and I think that's definitely different than a straight man’s health. We do different things. So, to find out my PCP wasn’t very personable, and I couldn't connect with him was very disappointing for me." (21, decline to state race/ethnicity, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP)

Both patients and providers agreed that making patients comfortable discussing sexual health during clinic appointments was an important strategy to improve this intervention. To do so, some patients suggested specifically recruiting clinicians that are members of the LGBT community:

“Discussing sexual health with somebody when I know that they're like a gay doctor that somehow puts me more at ease…you know that they're going to be more familiar with some of the issues you're talking about or potentially less judgmental about it.” (34, white, gay, linked to PrEP)

One patient noted a preference for an intervention provider who was an LGBT community member over a provider who simply had training in LGBT health.

“I was looking for a LGBT doctor…the clinic said, ‘we have, like, a network of doctors, of LGBT doctors’…I was casually talking to the doctor, and I mentioned, like, ‘oh, I thought it was great that, you know, it was a LGBT doctor,’ and he looked confused because he was not an LGBT doctor…He was like, ‘I’ve taken one certification class on LGBT issues’…that was not a positive experience…needless to say, I didn't do the PrEP referral…it was definitely a factor.” (30, Black, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP)

This quote depicts the importance to some sexual minority patients of having an LGBT clinician. The ability to link sexual minority patients with LGBT clinicians may be one promising way of increasing the acceptability of the screening and linkage intervention.

Providers spoke of reluctance and discomfort among their peers in discussing sexual behaviors and PrEP with patients during the initial patient visits. These experiences likely led to missed opportunities to implement the screening and linkage to PrEP intervention. Further, some providers noted that sexual behavior interventions have not succeeded in primary care in the past due to the stigma of sexual health:

“Sexual health is something that people struggle with…Just having condoms in clinic has not been well-received by people in power…I had somebody in power straight up email me and say that they didn't want to have condoms in clinic…So, you're not only dealing with barriers from the patient, you're dealing from barriers from our peers - our colleagues. We're dealing with a lot of perceptions, homophobia, internalized or otherwise.” (Primary Care Doctor)

These insights from both patients and providers suggest that stigmatization of sexual health was a meaningful barrier to the success of the intervention overall and may have contributed to the relatively low rates of screening (4.19%) among patients.

There were also cultural differences in experiences and perceptions of stigma, and in the likelihood of participating in a PrEP screening and linkage intervention, as one patient “I know p

“In communities of color…there is still a stigma in relation to the industrial healthcare system…especially in the Latino communities or African-American communities, preventative care is not something that you do.” (36, Hispanic/Latino, gay, linked to PrEP)

Relatedly, one provider discussed her perception that there are cultural differences among some older participants whereby they may experience more discomfort in answering sexual health questions:

“The younger males were open to PrEP and some of them even asked more information on it, but it was just most like the older…it was just too much information to reveal…So, I did have a little uncomfort with that.” (Primary Care Nurse)

In contrast to diverging perspectives on cost-related barriers discussed in the previous theme, both providers and patients shared similar perspectives on the impact of stigma, discomfort, and cultural barriers to the screening and linkage to PrEP intervention. This convergence suggests an opportunity to improve the intervention through stigma reduction and staffing of key stakeholders to improve the overall success of the intervention.

Logistical Hurdles and Streamlining the Intervention

Patients and providers agreed that several logistical barriers impacted the ability to implement the screening and linkage intervention in Project SLIP, although they differed in how they described the barriers and how best to ameliorate them. Patients listed many individual-level logistical difficulties that made the screening and linkage process highly inconvenient, even inaccessible. Some of these logistical barriers included being unable to make their appointment time at specialty HIV specialty care services, trouble locating the clinic, experiencing difficulties finding transportation to the clinic, not receiving a phone call for their follow-up appointment, and difficulties getting in touch with the clinic until they gave up. For example, one patient explained:

“I had to go all the way up to the clinic and then get tested for the same things literally, like, a week later…and I just remember, like, being frustrated…it should have been streamlined…I thought it was redundant.” (31, White, gay, linked to PrEP)

In general, patients found the process of having to attend botcan’t be informed about allh a primary care appointment and then a second appointment with HIV specialty care services as highly inconvenient. Several patients suggested creating a one-stop-shop where patients could see their PCP, get their blood work done, and see their PrEP doctor in one appointment or location. They indicated that this would reduce many of the logistical barriers such as coordinating appointment times, locating clinics, and transportation issues; all healthcare services could be accessed in one place and ideally, one visit. One patient explained how a one-stop-shop would be beneficial:

“The one-stop shop I think is also appealing because I would imagine that those who are working at that one-stop shop would be highly, you know, experienced and, you know, very familiar with the drug and the types of patients who are looking for that drug.” (30, Black, gay, eligible but not linked to PrEP)

As this patient describes, if this one-stop-shop went one step further by staffing providers who were trained and educated in PrEP specifically, it would also mitigate the other barrier of a lack of knowledge and education on PrEP.

Providers discussed encountering different, system-level logistical challenges than the patients brought up in their interviews. In particular, providers felt that clinic workload and staffing issues were the main logistical barriers to this intervention. For example, one provider explained:

“There are days where there's only one receptionist out there because they're short-staffed. So, I think a lot of times if there's patients pouring in, and you see a long line, you're just trying to check the patient in and do it as fast as you can. You don't really have the time to give out the (screener) to every single patient.” (Primary Care Medical Assistant)

Providers discussed how clinics that are short-staffed cause an increase in staff workload, which results in high demand for training new staff. However, there is oftentimes little supply of training due to time restraints.

“(New nurses) are not that familiar with (the study) …The nurses in the module filled them in, you know. And I had discussions with them. But it wasn’t the same as when you’re initially put into this pilot.” (Primary Care Administrator and Nurse)

This suggests that the cyclical nature of work environments with high staff workload is a barrier to this intervention. Providers felt that new staff members, in addition to having a lack of training, are also not familiar with the study and are likely less motivated to participate in the program.

Providers discussed a strategy that may overcome these salient barriers. Because staffing was a major concern, finding a way to make the screening process more effective and efficient came up often in provider interviews. One suggestion that providers had was to make this screening tool electronic or sent by mail prior to the appointment:

"It'd be great if when (patients) went up to the front and checked in, then at that time there was iPads that then they could hand to the patient, and the patient could go and sit down and fill out the questions on the iPad that then could be automatically uploaded… The other thing that you could do is send out mail. So, it could be sent - the questionnaire could be sent in advance in the mail." (Primary Care Doctor)

Both of the strategies suggested in this section, a one-stop-shop and using an electronic tool in screening, would improve the individual-level and system-level logistical barriers that both patients and providers brought up in these interviews.

The Lack of PrEP Knowledge and the Need for Education

Patients and providers had similar viewpoints on how knowledge about PrEP impacted their experience with this intervention. Both groups agreed that the provider’s lack of knowledge of PrEP was a significant barrier to being prescribed PrEP. Patients often said that they did not always feel that their providers explained PrEP comprehensively enough and some reported that they had to do their own research outside of their discussions with providers. For example, one patient explained:

“I know providers can’t be informed about all of the medication, and maybe he’s not well educated on (PrEP) not well educated on , as well. But, I mean, if they knew something and were able to communicate it, that probably would help a lot, just giving more information, general information, or even cost information.” (39, White, gay, ineligible for PrEP)

Providers themselves seemed well aware of the lack of knowledge on PrEP among their peers and suggested that further training and education is warranted.

“There’s not a huge knowledge base…I think every single primary care physician should be able to—should be competent to screen for PrEP and prescribe it at the very least.” (Primary Care Doctor)

Further, providers were also open about their own lack of knowledge and expressed concern that others in the clinic may be similarly ill-equipped.

“I took the time to actually read the information (provided by the intervention) and I actually learned some stuff myself about PrEP that I didn't know. So, I can't really say how many of that staff or the rest of the department and what person actually went in and read the whole thing. They get busy, but you’re just making sure that they're really aware of what's going on.” (Primary Care Nurse)

Patients suggested that providers need to be able to educate future patients on the benefits of PrEP, and explain the costs and benefits of taking PrEP and the possible side effects and/or interactions with other medications. Patients highlighted how important it is that their providers specifically be educated about PrEP:

“I think all kinds of doctors, internal medicine, family medicine, they need to be educated about (PrEP)…so when they do that flyer, they can talk to the patient about it, and that's where they determine whether they're interested.” (31, White, gay, linked to PrEP)

One specific strategy suggested by patients was to ensure that providers training other providers to do the intervention have experience and expertise in prescribing PrEP. Again, patients felt it would be important that the trainers/educators themselves were members of the communities that this intervention is targeted to, particularly sexual minorities:

“I feel like you need PrEP educators…you need people who mirror the communities that you want to target.” (36, Hispanic/Latino, gay, linked to PrEP)

Providers’ lack of knowledge about PrEP was found to be a significant system-level barrier to the implementation of this intervention. While all providers staffed in the study clinics were offered an educational training on providing PrEP and the SLIP intervention by an experienced PrEP provider before implementation, knowledge gaps remained and suggest ongoing training is warranted.

Patient lack of knowledge of PrEP was also discussed in this study. A suggestion presented by patients to improve PrEP knowledge and education was to implement social support groups among patients who have experience taking PrEP.

“(Patients) could see actual people who are using it and benefiting from it and hear from first-person accounts and how it’s helping them protect themselves…that would be a good way of reassuring first-time users that this is a safe and effective treatment.” (37, other race/ethnicity, straight, ineligible for PrEP)

Social support groups may be beneficial to not only educate future potential patients on how PrEP works and their experience taking PrEP, but it would also cultivate a supportive environment of peers. This may also help to reduce stigma and judgment in the clinic, which was a barrier discussed earlier.

Discussion

This study examined barriers and improvement strategies from the perspective of both patients and providers in real-time during a screening and linkage to PrEP from primary care pilot intervention. These barriers and strategies were grouped into four categories: 1) Financial Barriers: Individual- vs. Clinic-level Considerations 2) The Role of Stigma, Discomfort, and Cultural Factors 3) Logistical Hurdles and Streamlining the Intervention , and 4) The Lack of PrEP Knowledge and the Need for Education . These barriers and strategies oftentimes differed across these two groups. While these differing perspectives are not necessarily surprising, these differences have important implications for the future success and implementation of Project SLIP.

There were notable differences in patient and provider experiences, particularly around individual-level and system-level costs. Patients brought up several different financial barriers, such as the cost of prescriptions, which aligns with the prior research finding that expenses around healthcare and medications serve as a major barrier to uptake and adherence to medication regimens.30 Interestingly, we found that providers hardly ever discussed their patients’ experienced or perceived costs for PrEP, despite the frequent discussion of financial barriers during the patient interviews. Primary care providers working in large integrated healthcare systems may need additional training and education around the experienced and perceived costs associated with PrEP among their patients to help patients determine the actual costs based on their specific healthcare plan and the associated copays and medication costs.

On the other hand, providers focused largely on system-level costs, particularly in the form of staff workload. Providers mentioned being understaffed and short on time repeatedly throughout their interviews as their biggest barrier. Providers suggested several ways to improve the screening process in primary care settings to reduce staff burden, such as an electronic screening process that could be implemented in waiting rooms or sent to patients via email or webportal in advance of their primary care appointment, which would eliminate the need to request the screener be filled out in clinic. Previous studies have shown similar suggestions by providers as a way to eliminate the additional staff time needed to administer the screener while the patient is in the waiting room.31-34 Electronic methods are likely to decrease the burden on clinic staff while simultaneously reaching more patients and increasing perceptions of privacy when filling out the screener.

Further, providers discussed the need for consistent, trained, and available staff members to participate in the intervention, particularly as it related to new staff members that resulted from high turnover, or with float nurses. Previous studies with primary care providers have agreed that prescribing PrEP in their clinics is feasible, as long as funding and training on providing PrEP were also provided.35 To effectively implement a similar screening and linkage to PrEP intervention in primary care, it is of the utmost importance to ensure that clinic staffing needs are met. Patients and providers both agreed that there was a lack of PrEP knowledge in general among the providers. PCPs having limited experience and knowledge of PrEP is consistent with previous studies and has been shown to serve as a significant barrier to prescribing PrEP to their patients. 36, 37, 38 Because the likelihood of future PrEP prescribing has been shown to be highly associated with PCPs’ current PrEP knowledge,39 it is important to ensure a standard of PrEP knowledge among PCPs. Several patients in this study suggested requiring comprehensive PrEP training. Similarly, patients also spoke briefly about their own lack of knowledge of PrEP, with several suggesting that peer support groups with other patients taking PrEP may be one way to increase patients' knowledge. Previous studies among sexual minority men have shown improved adherence to PrEP with increased social support and social networks from peers in the LGBT community. 40, 41, 42, 43, 44. Adding support groups with other diverse sexual and gender minorities may be beneficial and should be considered in future intervention studies.

One notable barrier that patients discussed that was not mentioned by providers was the inconvenience of having multiple appointments in different locations. Patients emphasized the implementation strategy of a one-stop shop where they could be referred to and prescribed PrEP during a single visit. The one-stop shop model for PrEP has been largely underutilized and thus understudied, but has the potential to improve user experience, although staff and cost-effectiveness has not been established.45 This could be a direction for future implementation to reduce some of the patient-identified logistical and financial barriers related to multiple clinic appointments.

There were several limitations in this study. This study took place in one healthcare system, thus the results of this study are not generalizable to all primary care settings with different screening and linkage processes. While patients and providers self-reported their own experiences, the barriers described were highly consistent with prior studies, suggesting the validity of these findings. The provider sample size of this study was relatively small; however, interviews with providers and staff from a variety of roles were included in this study and all providers directly participated in the intervention. Similarly, the patients interviewed represented a diverse sample of SMM from the Los Angeles area. This allowed for representative thoughts from patients that are likely disproportionately affected by health disparities in access to care.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence for the acceptability and feasibility of a previously tested screening for PrEP implemented in primary care clinics and provides suggestions for ways of improving the screening and linkage to PrEP process. These qualitative interviews suggest that multiple barriers are impacting the process of providing PrEP in primary care, from screening to filling the prescription, and that there are also respective opportunities to improve this process.

It is important to note how patients’ and providers’ experiences were sometimes consistent and also differed at times across the various stages of the intervention. Taken together, these perspectives offer a more comprehensive picture of how future screening and linkage to PrEP interventions may be more equitably implemented.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R03DA043402, PI Storholm) with additional funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH12762, PI Storholm).. The authors would like to thank the providers and staff of KPSC who were willing to participate in this pilot and especially Dr. April Soto, Kim Luong, Marilyn Lansangan, and Dr. Richard Mehlman for their leadership and support for this project.

Abbreviations

References

- 1.V A Fonner, S L Dalglish, C E Kennedy, Baggaley R, K R O'Reilly. (2016) Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. , Aids 30(12), 1973-1983.

- 2.C I Okwundu, O A Uthman, C A Okoromah. (2012) Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for preventing HIV in high-risk individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (7). , Cd007189

- 3. (2021) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). PrEP for HIV Prevention in the U.S.https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/fact-sheets/hiv/PrEP-for-hiv-prevention-in-the-US-factsheet.html#

- 5.R Y Barrow, Ahmed F, G A Bolan, K A Workowski. (2020) Recommendations for Providing Quality Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinical Services. , MMWR Recomm Rep 68(5), 1-20.

- 6.Finocchario-Kessler S, Champassak S, M J Hoyt, Short W, Chakraborty R. (2016) Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for Safer Conception Among Serodifferent Couples:. Findings from Healthcare Providers Serving Patients with HIV in Seven US Cities. AIDS Patient Care STDS 30(3), 125-133.

- 7.A E Petroll, J L Walsh, J L Owczarzak, T L McAuliffe, L M Bogart. (2017) . PrEP Awareness, Familiarity, Comfort, and Prescribing Experience among US Primary Care Providers and HIV Specialists. AIDS Behav 21(5), 1256-1267.

- 8.Tellalian D, Maznavi K, U F Bredeek, W D Hardy. (2013) Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection: results of a survey of HIV healthcare providers evaluating their knowledge, attitudes, and prescribing practices. , AIDS Patient Care STDS 27(10), 553-559.

- 9.Bacon O, Gonzalez R, Andrew E, M B Potter, J R Iñiguez. (2017) Brief Report: Informing Strategies to Build PrEP Capacity Among San Francisco Bay Area Clinicians. , J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 74(2), 175-179.

- 10.Karim Abdool, Abdool Karim Q, S, J A Frohlich, A C Grobler et al. (2010) Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. , Science 329(5996), 1168-1174.

- 11.Bradley H, E M Rosenthal, M A Barranco, Udo T, P S Sullivan. (2020) Use of Population-Based Surveys for Estimating the Population Size of Persons Who Inject Drugs in the United States. J Infect Dis,222(Suppl5),218-s229.

- 12.M B Huang, Ye L, B Y Liang, C Y Ning, W et al. (2015) Characterizing the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States and China. , Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(1).

- 13.S A, J K Stockman. (2010) Epidemiology of HIV among injecting and non-injecting drug users: current trends and implications for interventions. , Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 7(2), 99-106.

- 14.M C Thigpen, P M Kebaabetswe, L A Paxton, D K Smith, C E Rose. (2012) Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. New England. , Journal of Medicine 367(5), 423-434.

- 15.L M Adams, B H. (2016) HIV providers' likelihood to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention differs by patient type: a short report. , AIDS care 28(9), 1154-1158.

- 16.O J Blackstock, B A Moore, G V Berkenblit, S K Calabrese, C O. (2017) A Cross-Sectional Online Survey of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Adoption Among Primary Care Physicians. , J Gen Intern Med 32(1), 62-70.

- 17.Krakower D, Ware N, J A Mitty, Maloney K, K H Mayer. (2014) HIV providers' perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. , AIDS Behav 18(9), 1712-1721.

- 18.D S Krakower, K M Maloney, Grasso C, Melbourne K, K H Mayer. (2016) Primary care clinicians' experiences prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis at a specialized community health centre in Boston: lessons from early adopters. , J Int AIDS Soc 19(1), 21165.

- 19.Boekeloo B O, Marx E S, Kral A H, Coughlin S C, Bowman M. (1991) Frequency and thoroughness of STD/HIV risk assessment by physicians in a high-risk metropolitan area. , Am J Public Health 81(12), 1645-1648.

- 20.S K Melville, S I Arbona, C L Jablonski, L I Kantor, J H Lee. (2004) Risk assessment practices of Texas private practitioners for sexually transmitted diseases. , Tex Med 100(6), 60-64.

- 21.M R Ashton, R L Cook, H C Wiesenfeld, M A Krohn, Zamborsky T. (2002) Primary care physician attitudes regarding sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 29(4), 246-251.

- 22.E D Storholm, Siconolfi D, Huang W, Towner W, D L Grant. (2021) Project SLIP: Implementation of a PrEP Screening and Linkage Intervention in Primary Care. , AIDS Behav 25(8), 2348-2357.

- 23.Permanente K.Our impact. in California.https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/our-story/news/public-policy-perspectives/our-impact/news-perspectives-on-public-policy-california

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. , Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101.

- 29.O’Connor C, Joffe H. (2020) Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. , International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19, 1609406919899220.

- 30.K H Mayer, Agwu A, Malebranche D. (2020) Barriers to the Wider Use of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in the United States: A Narrative Review. Advances in Therapy. 37(5), 1778-1811.

- 31.McNeely J, P C Kumar, Rieckmann T, Sedlander E, Farkas S. (2018) Barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of substance use screening in primary care clinics: a qualitative study of patients, providers, and staff. , Addict Sci Clin Pract 13(1), 8.

- 32.H I Meissner, C N Klabunde, Breen N, J M Zapka. (2012) Breast and colorectal cancer screening: U.S. primary care physicians' reports of barriers. , Am J Prev Med 43(6), 584-589.

- 33.J M Coughlin, Zang Y, Terranella S, Alex G, Karush J. (2020) Understanding barriers to lung cancer screening in primary care. , J Thorac Dis 12(5), 2536-2544.

- 34.A S O'Malley, Beaton E, K R Yabroff, Abramson R, Mandelblatt J. (2004) Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. , Prev Med 39(1), 56-63.

- 35.Blumenthal J, Jain S, Krakower D, Sun X, Young J. (2015) Knowledge is Power! Increased Provider Knowledge Scores Regarding Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) are Associated with Higher Rates of PrEP Prescription and Future Intent to Prescribe PrEP. , AIDS Behav 19(5), 802-810.

- 36.R M Pinto, K R Berringer, Melendez R, Mmeje O. (2018) Improving PrEP Implementation Through Multilevel Interventions: A Synthesis of the Literature. , AIDS Behav 22(11), 3681-3691.

- 37.E D Storholm, A J Ober, M L, Matthews L, Sargent M. (2021) Primary Care Providers' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs About HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): Informing Network-Based Interventions. , AIDS Educ Prev 33(4), 325-344.

- 38.Pleuhs B, K G Quinn, J L Walsh, A E Petroll, S A John. (2020) Health care provider barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS patient care and STDs. 34(3), 111-123.

- 39.Blumenthal J, Jain S, Krakower D, Sun X, Young J. (2015) Knowledge is Power! Increased Provider Knowledge Scores Regarding Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). are Associated with Higher Rates of PrEP Prescription and Future Intent to Prescribe PrEP. AIDS and Behavior 19(5), 802-810.

- 40.K G Quinn, Christenson E, Spector A, Amirkhanian Y, J A Kelly.The Influence of Peers on PrEP Perceptions and Use Among Young Black Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Examination. , Arch Sex Behav 49(6), 2129-2143.

- 41.Y T Chen, D T, Issema R, W C Goedel, Call.Social-Environmental Resilience, PrEP Uptake, and Viral Suppression among Young Black Men Who Have Sex with Men and Young Black Transgender Women: the Neighborhoods and Networks (N2) Study in Chicago. , J Urban Health 97(5), 728-738.

- 42.Wood S, Dowshen N, J A Bauermeister, Lalley-Chareczko L, Franklin J. (2020) Social Support Networks Among Young Men and Transgender Women of Color Receiving HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. , J Adolesc Health 66(3), 268-274.

- 43.Wood S, Gross R, J A Shea, J A Bauermeister, Franklin J. (2019) Barriers and Facilitators of PrEP Adherence for Young Men and Transgender Women of Color [Article]. , AIDS and Behavior 23(10), 2719-2729.

Cited by (5)

This article has been cited by 5 scholarly works according to:

Citing Articles:

AIDS Patient Care and STDs (2025) Crossref

AIDS Patient Care and STDs (2025) OpenAlex

Meredith E. Clement, Jennifer Thomas, Clare Kelsey, T. Jagneaux, Catherine O'Neal et al. - AIDS Patients Care and STDs (2025) Semantic Scholar

medRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) (2025) OpenAlex

Patient Preference and Adherence (2024) Crossref

Patient Preference and Adherence (2024) OpenAlex

Kirstin Kielhold, Erik D. Storholm, Hannah E Reynolds, Wilson Vincent, Daniel E Siconolfi et al. - Patient Preference and Adherence (2024) Semantic Scholar