Tomboys Revisited: A Retrospective Comparison of Childhood Behavioral Patterns in Lesbians and Transmen

Abstract

In 1979, a study conducted by Ehrhardt et al. retrospectively examined childhood behavioral patterns of 30 adults; 15 identified as lesbian women and 15 identified as transmen. All 30 adults had been assigned female at birth, and, as children, all were regarded as “tomboys.” The study found several key factors that distinguished the two cohorts. The goal of this study was to replicate and extend the 1979 study, utilizing a larger sample size and including a reference group of heterosexual women. Given the major social, technological, medical, and legal paradigm shifts that have occurred over the past four decades, we sought to determine if the previous findings still differentiate the cohorts. In light of the exponential rise in the number of gender diverse and dysphoric youth who request treatment, providing optimal, affirmative care and education is paramount, especially since many of these young people seek social and/or medical transition. Exploration of the early behavioral indices of the diverse trajectories may help to inform best practices for optimal care for these young people and their families.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Baoman Li, China Medical University, China.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2018 Randi Ettner, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

In 1979, Erhardt, Grisanti and McCauley retrospectively studied early childhood traits of 30 adults, all of whom were assigned female at birth, and most were considered “tomboys” during childhood and adolescence. Half of this group, 15 individuals, identified as lesbian women as adults. The other half transitioned, and identified as transmen. The investigators found several factors that differentiated the two groups. Most significantly, eighty percent of the transmen reported to have “cross-dressed” during childhood, which the investigators defined as having worn boys’ shoes and boys’ underwear. None of the lesbian women reported this behavior in childhood. Nearly all of the transmen (93%) and most of the lesbian women (67%) reported having been labeled as “tomboys” 1. Both groups displayed little interest in stereotypic maternal role play, i.e., playing with dolls or exhibiting an interest in babies 2, 3

The last four decades have ushered in a dramatic paradigm shift, challenging traditional stereotypic roles. Therefore, it seems reasonable that given the contemporary social landscape with less restrictive gender constructs, differences between groups would be correspondingly less dramatic. Thus, our primary goal of this study was to determine whether the findings of the Erhardt et. al. study remain relevant given the sweeping societal shifts. We employed a similar retrospective design to compare tomboy behavior, maternal emulation and play, and clothing preferences between lesbians and transmen. However, we aimed to extend these findings with the inclusion of a reference group of adult heterosexual women. We hypothesized that the findings of Erhardt et. al. would partially replicate. Specifically, we hypothesized that male clothing preference and maternal role-play would differ significantly between the lesbian women and transmen, but “tomboy” behavior would not differ, as physical activity and participation in sports have become vogue for all girls. Finally, we hypothesized that measures of clothing preference and maternal role-play would be significantly different between the reference group and the lesbian women and transmen groups.

Methods

Participants

The participants in this study were 161 adults, all of whom had been assigned female at birth. Of these 161 individuals, 45 identified as lesbian women, 50 as transmen, and 66 as heterosexual women. None of the participants identified as non-binary. The demographics of the three groups are provided in Table 1. Participants were recruited through mental health and general family practice clinics at several locations in the Midwest and the East Coast of the United States.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics between the groups| Transmen (n = 50) | Lesbians | Reference Group | |

| Age (mean, SD) years | 29.6 (13.6) | 51.7 (15.7) | 46.4 (14.1) |

| Ethnicity (n) | |||

| Caucasian | 44 | 38 | 61 |

| Black | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Hispanic | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Childhood Socioeconomic Status | |||

| Low | 10 | 13 | 5 |

| Middle | 33 | 29 | 53 |

| High | 7 | 3 | 8 |

| Highest Education (n) | |||

| Elementary / High School | 21 | 2 | 6 |

| Bachelors | 20 | 14 | 35 |

| Master’s / Doctorate | 7 | 29 | 25 |

| Partner Status | |||

| Single | 29 | 13 | 9 |

| Partner/Married | 19 | 30 | 49 |

| Divorced | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Widowed | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Questionnaire

To obtain information regarding demographic, behavioral, and gender-stereotypic preferences, a questionnaire was created and distributed, incorporating the parameters employed by the Erhardt et al study. The questionnaire consisted of 52 items, including questions regarding mental and physical health, and was designed to measure behaviors and preferences along a continuum. Content domains included childhood activities and behavior, childhood clothing preferences, and reaction to pubertal development.

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons of demographic variables between groups were evaluated using either an ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. To assess differences in behaviors and clothing preferences between the three groups via continuous variables, either ANOVAs (three groups) or t-tests (two groups) were performed. For categorical variables, chi-square analyses were performed.

Results

Demographics

There was a significant difference in age between the three groups (F2,158=30.5, p < 0.0001), with the transmen being younger than the lesbian women and the reference group. The lesbian women and the reference group had attained significantly higher levels of education (c2= 42.9, df = 4, p < 0.0001) and were more likely to have a partner (c2 = 16.6, df = 2, p < 0.001) compared to the transmen. The socioeconomic status of the household in which the participants were raised was quite similar across groups, with the exception that the lesbian women were slightly more likely to come from a lower socioeconomic status environment (c2= 9.7, df = 4, p < 0.05).

Transition Related Characteristics of the Transmen

The mean age in which the transmen first considered transition was 16.9 years; the mean age at which these individuals initiated transition was 23.4 years. The transition occurred at approximately the same time as the initiation of hormones (23.5 years). All of the individuals in this group had socially transitioned. All but four were receiving hormones. Twenty of the transmen underwent mastectomy; eight underwent hysterectomy; four underwent metoidioplasty; three participants had undergone vaginectomy, and one individual had undergone phalloplasty.

Tomboy Behavior

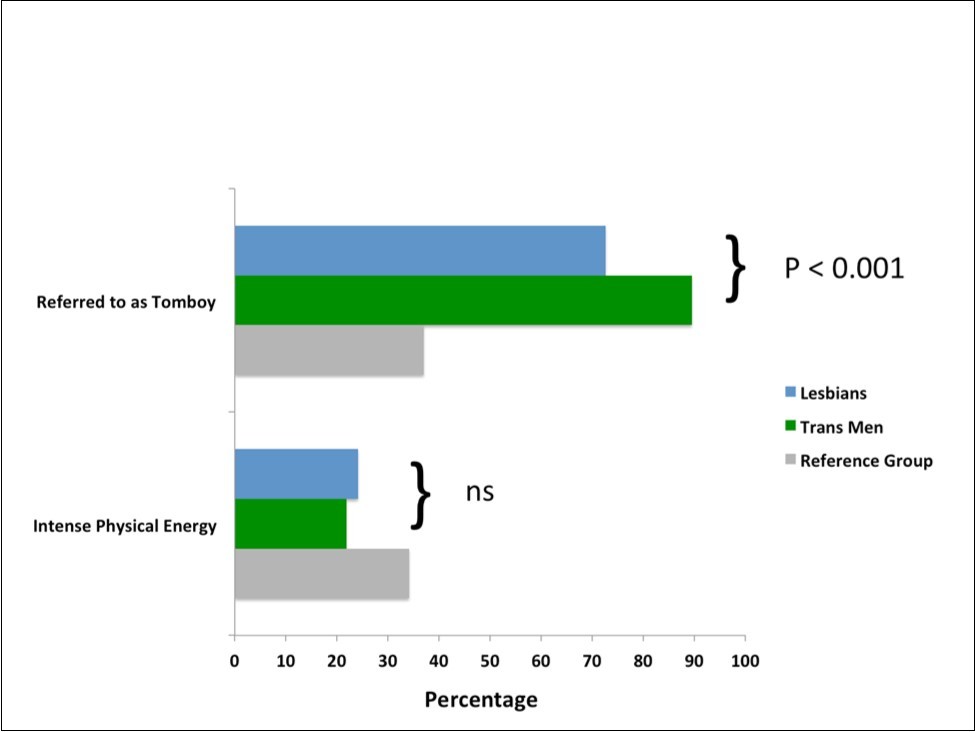

Participants were asked whether they had been regarded as tomboys during childhood and adolescence. Thirty percent of the reference group endorsed having received a label of “tomboy,” compared to 73% of lesbians and 90% of the transmen. All three comparisons were significant at (p<.001) Figure 1. There were no significant differences in the physical activity levels between the transmen and the lesbians, however both groups engaged in more intense physical activity in childhood than did the reference group (F2,158=5.3, p=0.006).

Figure 1.Tomboy labels and levels of energy in lesbian women, transmen, and the reference group.

Childhood Play and Interest in Child Care

There was a highly significant difference between the reference group compared to the lesbian women and the transmen in all areas related to interest in babies, maternal role-play, and doll play (Figure 2). Between transmen and lesbian women there were significant differences in maternal role play (χ2=9.2, df=1, p=0.002), paternal role play (χ2=12.4, df=1, p=0.0004) and play with cars and trucks (χ2=4.9, df=1, p=0.03), with the lesbian women having spent significantly more time playing “mommy” and the transmen preferring cars and trucks to dolls. There were no differences between lesbian women and transmen in desire to become a parent, interest in babies, or in enjoyment of babysitting.

Clothing Preferences

Three questions pertained to childhood clothing preferences. There were significant differences between the reference group, the lesbian women and the transmen in regards to their clothing choices in childhood (Figure 3). Thirty-seven percent of the reference group preferred plain clothing to fashionable clothing. This is in contrast to both the lesbian women (82%) and the transmen (80%): both groups preferred plain rather than stylish or “fancy” clothing as youngsters. Interestingly, there were highly significant differences in the desire to wear boys’ shoes and boys’ underwear. None of the reference group, and only 9% of the lesbian women stated the desire to wear boys’ underwear during childhood. This was in contrast to 78% of the transmen who preferred boys’ underwear (χ2=45.7, df=1, p=1.4x10-11). Six percent of the reference group, compared to 49% of lesbian women preferred to wear boys’ shoes as a child. This is in contrast to 90% of the transmen who had a marked preference for boys’ footwear (χ2=17.3, df=1, p=3.1x10-5).

Figure 3.Clothing preferences in lesbian women, transmen, and the reference group.

Hair Length

A continuous scale measuring the preference for short hair compared to long hair was highly significantly different between the three groups (F2,158=53.0, p=2.0x10-16). The reference group preferred long hair at a scale of 70.1, compared to 36.2 and 23.6 for the lesbian women and transmen, respectively. Contrasting the lesbian women to the transmen on this variable also proved significant. (t=2.4, df=90, p = 0.02).

Discussion

While many children who display gender atypical behavior do not identify as transgender in adulthood, there are few studies that examine sexual and gender identity trajectories in these children as they reach adulthood. In 1979, Erhard et al. reported that certain variables distinguished between two groups of adults who had been assigned female at birth, but exhibited gender atypical behavior in childhood. One group identified as lesbians, the other group identified as transgender. Using a retrospective analysis of specific childhood variables, the investigators concluded that childhood “cross-dressing” was strongly associated with gender transition at adulthood.

There has been a tectonic change in our knowledge and understanding of sexual orientation and gender identity in the ensuing four decades. In spite of these contextual changes, the current study, employing a much larger sample and a reference group, replicated the most salient findings of the 1979 study: Namely, amongst a group of children who were labeled “tomboys,” the preference for boys’ shoes and boys’ underwear in childhood was significantly associated with gender transition at maturity. In fact, none of the reference group had a desire to wear boys’ underwear, and only 9% of the lesbian women desired to do so, in contrast to 78% of the transmen. It is reductionistic to conclude that specific childhood behaviors or preferences, in and of themselves, can predict future outcomes. But the robustness of the data indicating that desire to wear boys’ underwear is consistently related to gender transition is indeed striking.

Children become aware of gender categories at an early age 2. At two years, toddlers begin to use gender stereotypes in play and by age five, preference for stereotypic toys is fairly well established 4. Three-year-olds recognize that there are two distinct groups, and certain clothing styles and/or colors, hairstyle and/or hair length are social signifiers that denote gender group membership 5. Often, the display itself serves as a proxy for gender, causing very young children to arrive at unique interpretations. For example, a four-year-old child may announce that an androgynous appearing teacher is “a girl because he wears earrings.” Similarly, four to six-year olds understand “gender scripts.” Instead of grouping items, they begin to categorize activities into gender categories. So, a person putting on make-up is deemed female. By age six to seven, youngsters recognize that gender is constant, and a man putting on make-up is a man.

In tandem with the awareness that males and females can be differentiated based on external presentation, the child has the burgeoning phenomenological sense of comfort or discomfort with their own assigned category, i.e. the development of gender identity. One participant in the lesbian group commented, “As a child I was happy if someone thought I was a boy. Sometimes I wished I was a boy, but I didn’t really want to be a boy once I got a little older.” This sentiment is consistent with the Steensma et al observations. They found that gender non-conforming girls who in early childhood claimed that they felt they were boys were more likely to transition than those that only wished they were boys 6, 7, 8.

For the child who experiences gender incongruity, adoption of the emblems, representations and play activities that cue the relevant gender can be intensely pursued. The literature documents that those children who were assigned female at birth and later transition are more likely to experience intense gender dysphoria in childhood 6, 7, 8. The presence of such strong convictions early in life, coupled with a growing assemblage of research, points to genetic and neurodevelopmental explanations for this cross-sex development of gender identity 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18.

Given that external displays equate to gender categorization, why is it that underwear, which is non-visible, is retrospectively highly associated with a transgender identity in both studies? One explanation is that these displays of gender non-conformity often arouse the shame affect. Children who exhibit gender atypical behaviors or expressions are often rebuked by family, peers or community 5, 19, 20, although recent years have ushered in greater understanding and acceptance of gender diversity. However, in the context of less accepting environments, underwear may be a private declaration of identity that reduces the potential for shame. Additionally, with the availability of more gender-neutral clothing, underwear remains quite gender specific. Furthermore, young children often employ self-soothing and tactile talismans, and these concrete items can be more satisfying than role-playing or fantasy activities wherein the child assumes the desired gender. Perhaps most importantly, undergarments obscure and are proximate to the genitals, an area of the body that can be visually disturbing for a gender dysphoric child. One intensely dysphoric six year old, assigned female at birth, cried whenever she was naked.

Future longitudinal studies that examine these variables prospectively will help elucidate and potentially parse the complexities of identity formation, as well as the specificity of our findings. However, large population-based studies would be required to achieve an adequate sample size to test these factors within the general population. While much remains unknown, what is known is that the overarching goal is reducing stigma, fostering resilience and providing support and care for these children and their families.

References

- 1.Ehrhardt A, Grisanti G, McCauley A. (1979) Female-to-male transsexuals compared to lesbians: behavioral patterns of childhood and adolescent development. , Archives of Sexual Behavior 8(6), 481-490.

- 2.Halim M, Ruble D. (2010) Gender identity and stereotyping in early and middle childhood. in Chrisler & McCreary (Eds.), Handbook of gender research in psychology.New York.Springer .

- 3.Koehler A, Richter-Appelt H, Cerwenka A, Kreukels B, Watzlawik M. (2016) Recalled gender-related play behavior and peer-group preferences in childhood and adolescence among adults applying for gender-affirming treatment. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 32(2), 210-226.

- 4.Golombok S, Rust J, Zervoulis K, Croudace T, Golding J et al. (2008) Developmental trajectories of sex-typed behavior in boys and girls: A longitudinal general population study of children aged 2.5-8 years. , Child Development 79(5), 1583-1593.

- 5.Ruble D, Taylor L, Cyphers L, Greulich F, Lurye L et al. (2007) The role of gender constancy in early gender development. , Child Development 78(4), 1121-1136.

- 6.Steensma T, Biemond R, F de Boer, Cohen-Kettenis P. (2011) Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: a qualitative follow-up study. , Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 16(4), 499-516.

- 7.Steensma T, McGuire J, Kreukels B, Beekman A, Cohen-Kettenis P. (2013) Factors associated with desistance and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: a quantitative follow-up study. , Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 52(6), 582-590.

- 8.Steensma T, Ende J Verhulst van der, Cohen-Kettenis F, P. (2013) Gender variance in childhood and sexual orientation in adulthood: A prospective study. , Journal of Sexual Medicine 10(11), 2723-2733.

- 9.Diamond M. (2013) Transsexuality among twins: identity concordance, transition, rearing, and orientation. , Int J Trans 14, 24-28.

- 10.Guillamon A, Junque C, Gomez-Gil E. (2016) A review on the status of brain structure research in transsexualism. , Archives of Sexual Behavior 45(7), 1615-1648.

- 11.Hines M. (2011) Gender development and the human brain. , Annual Review of Neuroscience 34, 69-88.

- 12.Kula K, Dulko S, Pawlikowski M. (1986) A nonspecific disturbance of the gonadostat in women with transsexualism and isolated hypergonadotropism in the male-to-female disturbance of gender identity. , Exp Clin Endocrinol 87(1), 8-14.

- 13.Luders E, Narr K L, Thompson P M, Rex D E, Woods R P et al. (2006) Gender effects on cortical thickness and the influence of scaling. , Human Beh Mapping 27, 314-332.

- 14.Rametti G, Carrillo B, Gomez-Gil E, Junque C, Segovia S et al. (2011) White matter microstructure in female to male transsexuals before cross-sex hormonal treatment: A diffusion tensor imaging study. , J Psychiatric Res 45, 199-204.

- 15.Zhou J N, Hofman M A, Gooren L J. (1995) A sex difference in the human brain and its relation to transsexuality. , Nature 378(6552), 68-70.

- 16.Zubiaurre-Elorza L, Junque C, Gomez-Gil E, Segovia S, Carrillo B et al. (2013) Cortical thickness in untreated transsexuals. , Cerebral Cortex 23, 2855-2862.

- 17.Zubiaurre-Elorza L, Junque C, Gomez-Gil E, Guillamon A. (2014) Effects of cross-sex hormone treatment on cortical thickness in transsexual individuals. , J Sex Med 11, 1248-1261.

- 18.Bentz E K, Hefler L A, Kaufman U. (2008) A polymorphism of the CYP17 gene related to sex steroid metabolism is associated with female-to-male but not male-to-female transsexualism. , Fertil Steril 90(1), 56-59.

Cited by (8)

This article has been cited by 8 scholarly works according to:

Citing Articles:

Chinese Physics C (2021) Crossref

Chinese Physics C (2021) OpenAlex

F. An, A. Balantekin, H. Band, M. Bishai, S. Blyth et al. - Chinese Physics C, High Energy Physics & Nuclear Physics (2020) Semantic Scholar

E. Samigullin - Journal of Physics: Conference Series (2019) Semantic Scholar

Journal of Physics: Conference Series (2019) Crossref

Journal of Physics Conference Series (2019) OpenAlex

C. Vigorito - Journal of Physics: Conference Series (2019) Semantic Scholar

Journal of Physics Conference Series (2019) OpenAlex

J. Bautista, N. Busca, J. Guy, J. Rich, M. Blomqvist et al. - (2017) Semantic Scholar

Astronomy and Astrophysics (2017) OpenAlex